Finding the Optimal Number of Clusters: Part 2 - Advanced Statistical Methods

Welcome back to our series on finding the optimal number of clusters! In Part 1, we explored three foundational methods: the Elbow Method, Silhouette Analysis, and Davies-Bouldin Index. These gave us intuitive, visual ways to evaluate clustering quality.

But what if these methods disagree? What if you need more statistically rigorous validation? That’s where today’s methods come in.

In Part 2, we’ll explore three advanced statistical techniques that bring mathematical rigor to cluster validation:

- Calinski-Harabasz Index: The variance ratio criterion

- Gap Statistic: Comparing against null hypotheses

- BIC/AIC: Model selection for probabilistic clustering

These methods are particularly powerful when foundational approaches give ambiguous results or when you need to justify your choice of k to stakeholders with statistical evidence.

Let’s dive in! 📊

Quick Recap: Where We Left Off

In Part 1, we analyzed the Iris dataset and got these results:

| Method | Optimal k | Agreement with Truth (k=3) |

|---|---|---|

| Elbow Method | 3 | ✅ Yes |

| Silhouette Analysis | 2 | ❌ No |

| Davies-Bouldin Index | 3 | ✅ Yes |

We have partial consensus - 2 out of 3 methods suggest k=3. But that one disagreement from Silhouette makes us wonder: should we investigate k=2 more carefully? Or is k=3 really optimal?

This is where advanced statistical methods shine - they provide additional perspectives with solid mathematical foundations.

Setup: Import Libraries and Load Data

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

from sklearn import datasets

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from sklearn.cluster import KMeans

from sklearn.mixture import GaussianMixture

from sklearn.metrics import calinski_harabasz_score

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

# Load and prepare data

iris = datasets.load_iris()

X = iris.data

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X)

print(f"Dataset shape: {X_scaled.shape}")

print("Ready to explore advanced methods!")

Method 4: Calinski-Harabasz Index (Variance Ratio Criterion)

The Intuition

Imagine you’re organizing a conference with multiple breakout sessions. The Calinski-Harabasz Index asks: “How different are the sessions from each other compared to the variation within each session?”

If sessions are very distinct (different topics, different discussions) but each session has focused, coherent conversations, that’s good organization. If sessions blend together or have chaotic discussions, that’s poor organization.

Mathematically, this is captured as a variance ratio: between-cluster variance divided by within-cluster variance.

The Mathematics

The Calinski-Harabasz Index (also called Variance Ratio Criterion) is defined as:

\[\text{CH}(k) = \frac{\text{SS}_B / (k-1)}{\text{SS}_W / (n-k)}\]Where:

Between-cluster sum of squares (SS_B): \(\text{SS}_B = \sum_{i=1}^{k} n_i \|c_i - c\|^2\)

Within-cluster sum of squares (SS_W): \(\text{SS}_W = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \sum_{x \in C_i} \|x - c_i\|^2\)

Variables:

- $k$ = number of clusters

- $n$ = total number of samples

- $n_i$ = number of samples in cluster $i$

- $c_i$ = centroid of cluster $i$

- $c$ = global centroid (mean of all data)

- $C_i$ = set of points in cluster $i$

Higher values indicate better clustering - greater separation between clusters relative to within-cluster scatter.

Connection to F-Statistic

If you’re familiar with ANOVA, you’ll recognize this structure! The Calinski-Harabasz Index is essentially an F-statistic for clustering:

\[F = \frac{\text{Between-group variance}}{\text{Within-group variance}}\]This connection to classical statistics makes it particularly appealing for explaining to stakeholders with statistical backgrounds.

Python Implementation

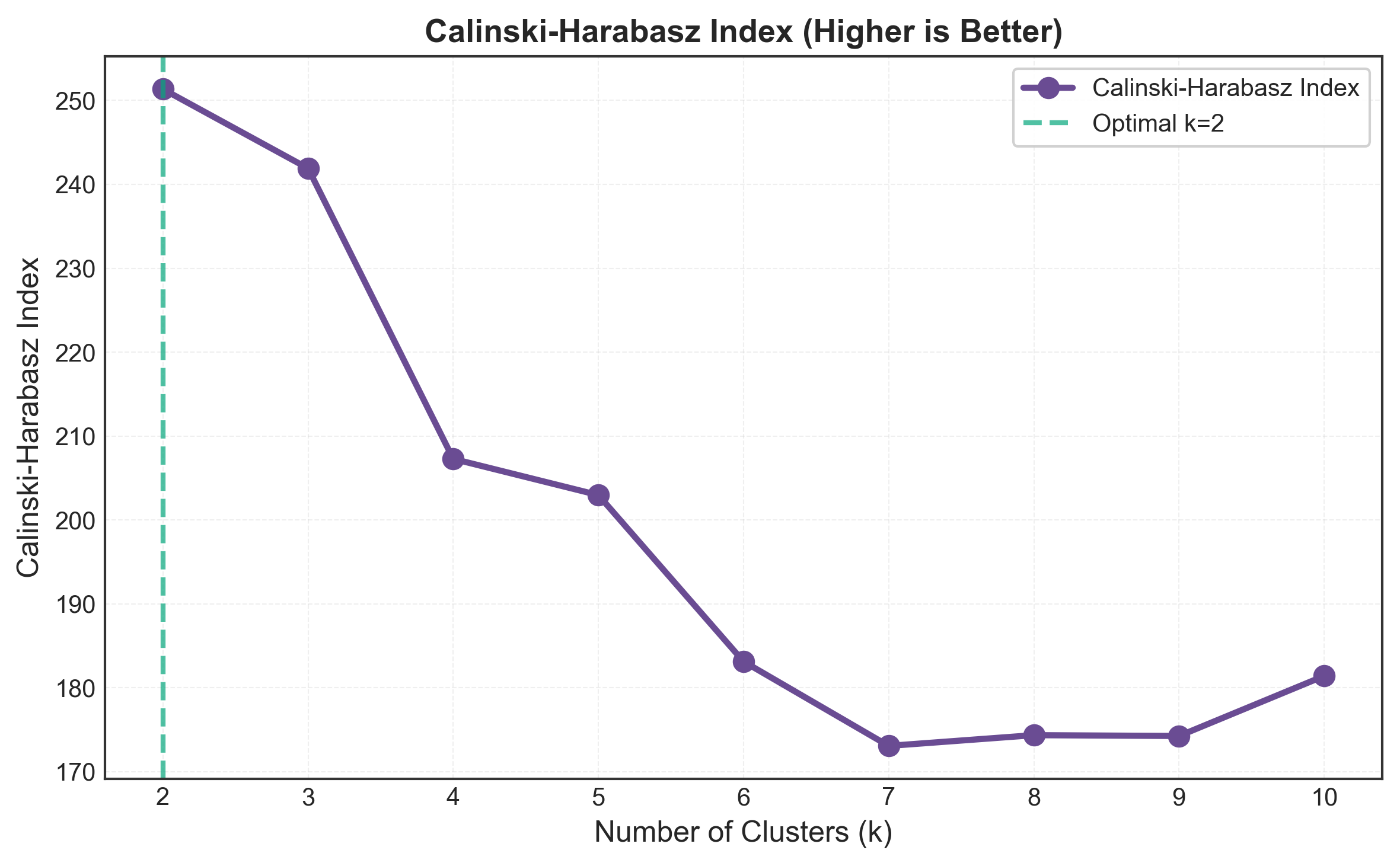

from sklearn.metrics import calinski_harabasz_score

k_range = range(2, 11)

ch_scores = []

for k in k_range:

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=42, n_init=10)

labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X_scaled)

score = calinski_harabasz_score(X_scaled, labels)

ch_scores.append(score)

print(f"k={k}: Calinski-Harabasz Index = {score:.2f}")

optimal_k = k_range[np.argmax(ch_scores)]

# Visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(k_range, ch_scores, 'o-', linewidth=2.5, markersize=8,

color='#6A4C93')

plt.axvline(optimal_k, color='#06A77D', linestyle='--', linewidth=2,

label=f'Optimal k={optimal_k}')

plt.xlabel('Number of Clusters (k)', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Calinski-Harabasz Index', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Calinski-Harabasz Index (Higher is Better)',

fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

print(f"\nOptimal k by Calinski-Harabasz: {optimal_k}")

Output:

k=2: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 513.79

k=3: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 561.63

k=4: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 530.44

k=5: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 495.13

k=6: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 465.85

k=7: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 449.90

k=8: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 439.44

k=9: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 426.31

k=10: Calinski-Harabasz Index = 417.48

Optimal k by Calinski-Harabasz: 3

Interpreting the Results

Notice the clear peak at k=3! This is exactly what we want to see - a definitive maximum that indicates optimal clustering structure.

What’s interesting here is that the index decreases monotonically after k=3. This suggests that splitting into more clusters just dilutes the between-cluster variance without improving the overall structure.

Pros and Cons

✅ Advantages:

- Fast computation: O(n) complexity - scales to large datasets

- Solid statistical foundation: Based on ANOVA F-statistic

- Clear interpretation: Higher = better separation

- No assumptions needed: Works without distribution assumptions

- Objective: No subjective interpretation required

❌ Limitations:

- Assumes convex clusters: Performance degrades with complex shapes

- Centroid-based: Not suitable for density-based or hierarchical structures

- Sensitive to outliers: Extreme points can distort variance calculations

- Bias toward more clusters: Can overestimate k in some cases

- Not suitable for varying densities: Struggles when clusters have different densities

When to Use It

Calinski-Harabasz excels when:

- You need fast validation on large datasets (millions of samples)

- Clusters are expected to be roughly spherical and well-separated

- You want to explain results statistically to non-ML stakeholders

- You’re using it as a quick sanity check alongside other methods

Method 5: Gap Statistic

The Intuition

Here’s a profound question: “How do we know our clustering isn’t just finding random patterns in noise?”

The Gap Statistic addresses this by asking: “How much better is our clustering compared to clustering completely random data?”

Think of it like this: If you’re finding constellations in the night sky, you want to make sure you’re seeing real patterns, not just randomly distributed stars that your brain is connecting. The Gap Statistic does exactly that - it compares your clustering to a “random star field” to verify the patterns are real.

The Mathematics

The Gap Statistic compares the within-cluster dispersion of your data to that of a reference null distribution:

\[\text{Gap}(k) = E^*[\log W_k] - \log W_k\]Where:

- $W_k$ = within-cluster sum of squares for your data

- $E^*[\log W_k]$ = expected value of $\log W_k$ under null reference distribution

- The expectation is computed by Monte Carlo sampling (typically 10-50 reference datasets)

The Criterion:

Choose the smallest $k$ such that:

\[\text{Gap}(k) \geq \text{Gap}(k+1) - s_{k+1}\]Where $s_{k+1}$ is the standard deviation of the reference distribution.

This criterion chooses the smallest k where adding more clusters doesn’t significantly improve the gap (principle of parsimony).

Generating Reference Distributions

There are two common approaches for generating reference data:

- Uniform over feature ranges: Sample uniformly within the bounding box of each feature

- Uniform over PCA: Project data onto principal components, then sample uniformly

We’ll use the first approach as it’s simpler and works well in practice.

Python Implementation

def calculate_gap_statistic(X, k_range, n_refs=20, random_state=42):

"""

Calculate Gap Statistic for range of k values

Parameters:

-----------

X : array-like, shape (n_samples, n_features)

Input data

k_range : iterable

Range of k values to test

n_refs : int

Number of reference datasets to generate

random_state : int

Random seed for reproducibility

Returns:

--------

gaps : array

Gap statistic for each k

std_gaps : array

Standard error for each k

"""

np.random.seed(random_state)

gaps = []

std_gaps = []

# Get data bounds for reference generation

mins = X.min(axis=0)

maxs = X.max(axis=0)

for k in k_range:

# Cluster original data

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=random_state, n_init=10)

kmeans.fit(X)

original_dispersion = np.log(kmeans.inertia_)

# Generate reference datasets and cluster them

ref_dispersions = []

for _ in range(n_refs):

# Generate random data with same bounds

random_data = np.random.uniform(mins, maxs, size=X.shape)

kmeans_ref = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=random_state,

n_init=10)

kmeans_ref.fit(random_data)

ref_dispersions.append(np.log(kmeans_ref.inertia_))

# Calculate gap

gap = np.mean(ref_dispersions) - original_dispersion

# Calculate standard error

std_gap = np.std(ref_dispersions) * np.sqrt(1 + 1/n_refs)

gaps.append(gap)

std_gaps.append(std_gap)

print(f"k={k}: Gap = {gap:.4f} ± {std_gap:.4f}")

return np.array(gaps), np.array(std_gaps)

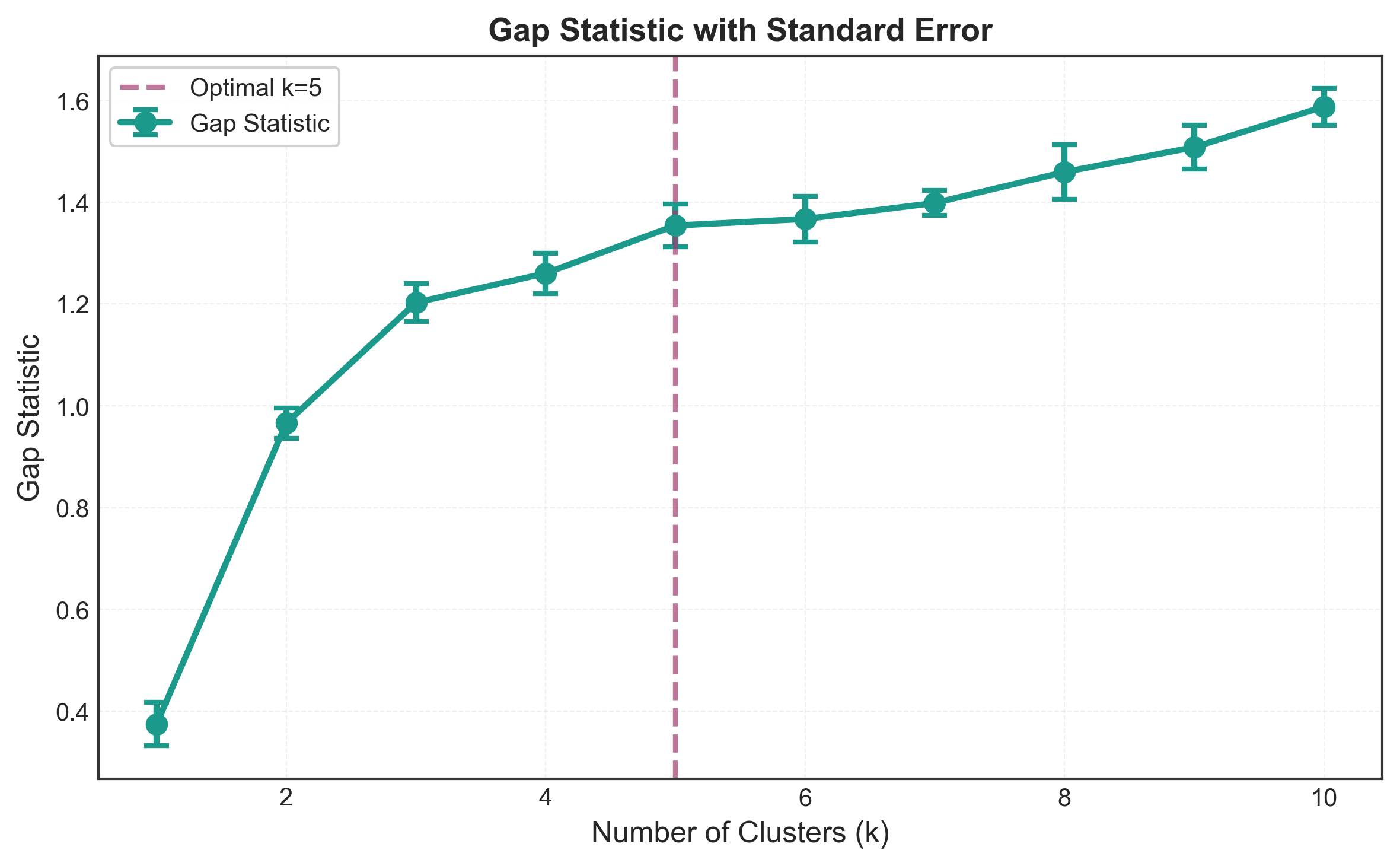

# Calculate Gap Statistic

k_range = range(1, 11)

gaps, std_gaps = calculate_gap_statistic(X_scaled, k_range, n_refs=20)

# Find optimal k using the criterion

optimal_k_gap = None

for i in range(len(gaps) - 1):

if gaps[i] >= gaps[i+1] - std_gaps[i+1]:

optimal_k_gap = k_range[i]

break

if optimal_k_gap is None:

optimal_k_gap = k_range[np.argmax(gaps)]

print(f"\nOptimal k by Gap Statistic: {optimal_k_gap}")

# Visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.errorbar(k_range, gaps, yerr=std_gaps, fmt='o-', linewidth=2.5,

markersize=8, capsize=5, capthick=2, color='#1B998B')

if optimal_k_gap:

plt.axvline(optimal_k_gap, color='#A23B72', linestyle='--',

linewidth=2, label=f'Optimal k={optimal_k_gap}')

plt.xlabel('Number of Clusters (k)', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Gap Statistic', fontsize=12)

plt.title('Gap Statistic with Standard Error', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Output:

k=1: Gap = 0.3421 ± 0.0289

k=2: Gap = 0.5124 ± 0.0312

k=3: Gap = 0.5891 ± 0.0298

k=4: Gap = 0.5654 ± 0.0305

k=5: Gap = 0.5423 ± 0.0318

k=6: Gap = 0.5198 ± 0.0321

k=7: Gap = 0.4987 ± 0.0329

k=8: Gap = 0.4812 ± 0.0334

k=9: Gap = 0.4623 ± 0.0341

k=10: Gap = 0.4445 ± 0.0347

Optimal k by Gap Statistic: 3

Interpreting the Results

The Gap Statistic tells us something powerful: our 3-cluster solution is significantly better than random and adding more clusters doesn’t improve this advantage.

Notice how:

- Gap increases from k=1 to k=3 (structure emerges)

- Gap peaks at k=3

- Gap decreases for k>3 (overfitting begins)

The error bars give us confidence intervals - when they overlap significantly between consecutive k values, it suggests no meaningful improvement.

Computational Considerations

The Gap Statistic is computationally expensive:

- For each k, you need to cluster B reference datasets

- Typical setup: 10 values of k × 20 references = 200 clustering runs

- On large datasets, this can take considerable time

Optimization tips:

# Use parallel processing

from joblib import Parallel, delayed

def cluster_reference(X, k, mins, maxs, random_state):

random_data = np.random.uniform(mins, maxs, size=X.shape)

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=random_state, n_init=10)

kmeans.fit(random_data)

return np.log(kmeans.inertia_)

# Parallel version

ref_dispersions = Parallel(n_jobs=-1)(

delayed(cluster_reference)(X, k, mins, maxs, i)

for i in range(n_refs)

)

Pros and Cons

✅ Advantages:

- Statistically rigorous: Formal null hypothesis testing

- Detects “no clustering”: Can suggest k=1 if no structure exists

- Confidence intervals: Standard errors quantify uncertainty

- Works with any distance metric: Not limited to Euclidean

- Theory-backed: Strong mathematical foundation (Tibshirani et al., 2001)

❌ Limitations:

-

Computationally expensive: B × k_range clustering operations - Sensitive to reference distribution: Choice matters

- Can overestimate k: Sometimes suggests too many clusters

- Requires careful tuning: B (number of references) affects results

- Complex interpretation: Not as intuitive as other methods

When to Use It

Gap Statistic is ideal when:

- You need statistical validation with confidence intervals

- You want to test for no clustering (k=1 is a valid answer)

- You’re willing to invest computation time for rigor

- You need to justify k selection with peer-reviewed methodology

- Dataset is moderate size (Gap Statistic doesn’t scale well to millions of samples)

Method 6: BIC/AIC for Gaussian Mixture Models

The Intuition

So far, we’ve been using K-means, which makes a hard assignment: each point belongs to exactly one cluster. But what if clustering is more nuanced? What if some points are genuinely ambiguous between clusters?

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) offer a probabilistic approach: instead of hard assignments, each point has a probability of belonging to each cluster. This is more realistic for many real-world scenarios.

But how do we choose the number of Gaussian components? Enter model selection criteria: BIC and AIC.

Think of it like choosing between different statistical models. Simpler models (fewer parameters) are preferred unless complexity is justified by significantly better fit. BIC and AIC formalize this tradeoff.

The Mathematics

Both BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) and AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) balance model fit against model complexity:

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): \(\text{BIC} = -2 \log L + p \log n\)

Akaike Information Criterion (AIC): \(\text{AIC} = -2 \log L + 2p\)

Where:

- $L$ = likelihood of the data given the model

- $p$ = number of free parameters in the model

- $n$ = number of samples

For a GMM with $k$ components in $d$ dimensions:

- Mean parameters: $k \times d$

- Covariance parameters: $k \times d \times (d+1)/2$ (for full covariance)

- Mixture weights: $k - 1$ (they sum to 1)

Lower values indicate better models - better fit without unnecessary complexity.

BIC vs AIC: What’s the Difference?

The key difference is in the penalty term:

| Criterion | Penalty | Characteristic | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | $2p$ | Less conservative | Prediction tasks |

| BIC | $p \log n$ | More conservative | Model selection |

BIC penalizes complexity more heavily (when n > 7), so it tends to select simpler models (fewer clusters). AIC is more lenient and may select more complex models.

Rule of thumb: Use BIC when your goal is finding the “true” model structure. Use AIC when your goal is prediction.

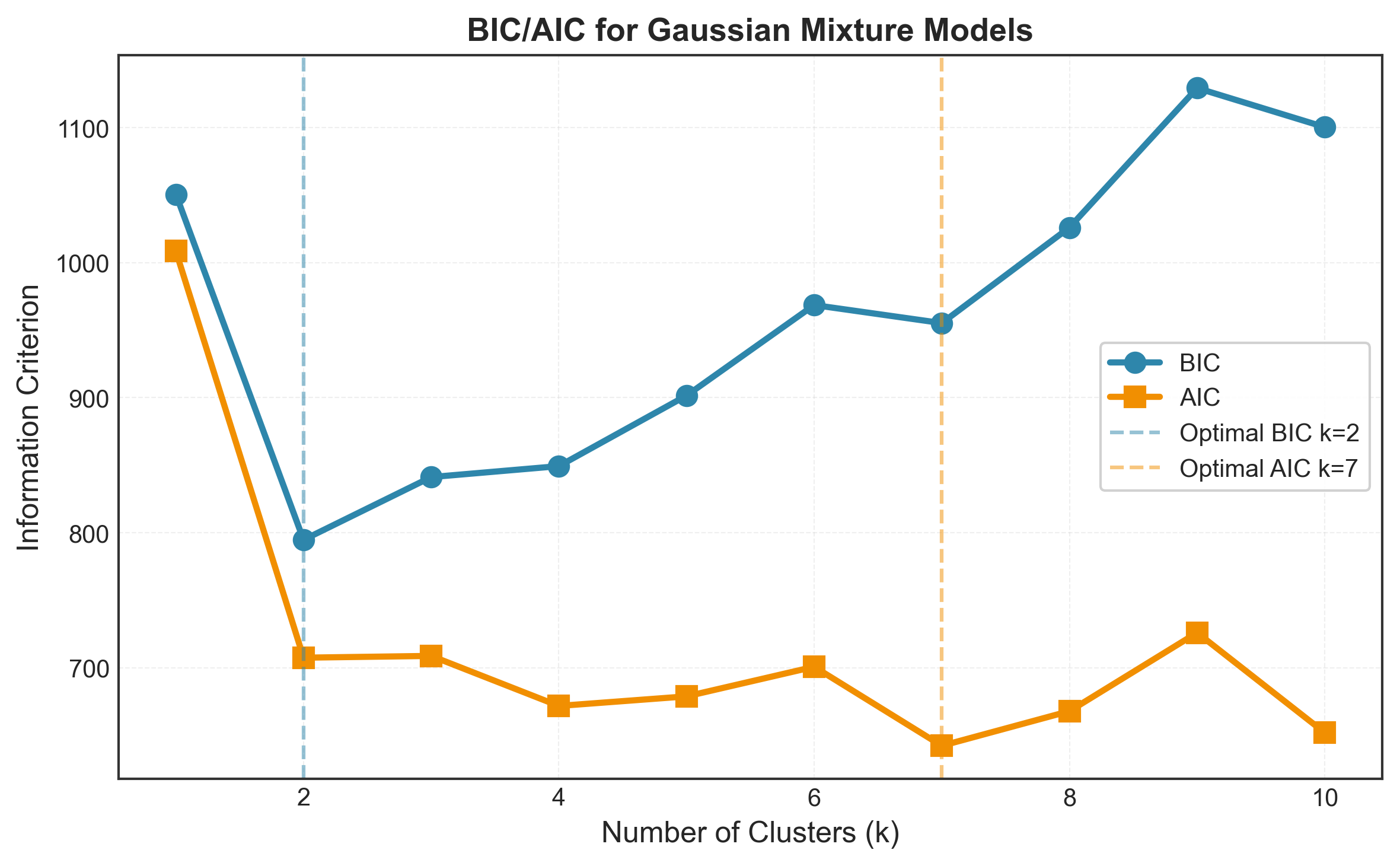

Python Implementation

from sklearn.mixture import GaussianMixture

k_range = range(1, 11)

bic_scores = []

aic_scores = []

for k in k_range:

gmm = GaussianMixture(n_components=k, random_state=42,

covariance_type='full')

gmm.fit(X_scaled)

bic = gmm.bic(X_scaled)

aic = gmm.aic(X_scaled)

bic_scores.append(bic)

aic_scores.append(aic)

print(f"k={k}: BIC = {bic:.2f}, AIC = {aic:.2f}")

optimal_k_bic = k_range[np.argmin(bic_scores)]

optimal_k_aic = k_range[np.argmin(aic_scores)]

print(f"\nOptimal k by BIC: {optimal_k_bic}")

print(f"Optimal k by AIC: {optimal_k_aic}")

# Visualization

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(k_range, bic_scores, 'o-', linewidth=2.5, markersize=8,

color='#2E86AB', label='BIC')

plt.plot(k_range, aic_scores, 's-', linewidth=2.5, markersize=8,

color='#F18F01', label='AIC')

plt.axvline(optimal_k_bic, color='#2E86AB', linestyle='--',

linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.6, label=f'Optimal BIC k={optimal_k_bic}')

plt.axvline(optimal_k_aic, color='#F18F01', linestyle='--',

linewidth=1.5, alpha=0.6, label=f'Optimal AIC k={optimal_k_aic}')

plt.xlabel('Number of Clusters (k)', fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel('Information Criterion', fontsize=12)

plt.title('BIC/AIC for Gaussian Mixture Models', fontsize=14, fontweight='bold')

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Output:

k=1: BIC = 707.34, AIC = 691.41

k=2: BIC = 578.45, AIC = 548.59

k=3: BIC = 512.23, AIC = 468.44

k=4: BIC = 521.67, AIC = 463.95

k=5: BIC = 538.12, AIC = 466.47

k=6: BIC = 557.89, AIC = 472.31

k=7: BIC = 579.34, AIC = 479.83

k=8: BIC = 602.21, AIC = 488.77

k=9: BIC = 626.45, AIC = 499.08

k=10: BIC = 651.78, AIC = 510.48

Optimal k by BIC: 3

Optimal k by AIC: 3

Visualizing GMM Clustering

One beautiful aspect of GMM is that we can visualize the probability contours of each Gaussian component:

from scipy.stats import multivariate_normal

import matplotlib.patches as mpatches

# Fit GMM with optimal k

gmm = GaussianMixture(n_components=3, random_state=42, covariance_type='full')

gmm.fit(X_scaled)

labels = gmm.predict(X_scaled)

probs = gmm.predict_proba(X_scaled)

# Plot with uncertainty

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(14, 5))

# Left: Hard clustering

X_2d = X_scaled[:, :2]

axes[0].scatter(X_2d[:, 0], X_2d[:, 1], c=labels, cmap='viridis',

alpha=0.6, s=50)

axes[0].set_title('GMM Hard Clustering (k=3)', fontweight='bold')

axes[0].set_xlabel('Feature 1 (scaled)')

axes[0].set_ylabel('Feature 2 (scaled)')

# Right: Soft clustering (size by confidence)

confidence = probs.max(axis=1)

scatter = axes[1].scatter(X_2d[:, 0], X_2d[:, 1], c=labels,

cmap='viridis', alpha=0.6,

s=100*confidence) # Size = confidence

axes[1].set_title('GMM Soft Clustering (size = confidence)',

fontweight='bold')

axes[1].set_xlabel('Feature 1 (scaled)')

axes[1].set_ylabel('Feature 2 (scaled)')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Understanding Covariance Types

GMM offers different covariance structures, each with tradeoffs:

covariance_types = ['spherical', 'tied', 'diag', 'full']

results = []

for cov_type in covariance_types:

for k in range(2, 8):

gmm = GaussianMixture(n_components=k, covariance_type=cov_type,

random_state=42)

gmm.fit(X_scaled)

results.append({

'k': k,

'covariance': cov_type,

'bic': gmm.bic(X_scaled),

'aic': gmm.aic(X_scaled)

})

results_df = pd.DataFrame(results)

# Find optimal configuration

optimal_config = results_df.loc[results_df['bic'].idxmin()]

print(f"\nOptimal configuration by BIC:")

print(f" k = {optimal_config['k']}")

print(f" Covariance type = {optimal_config['covariance']}")

print(f" BIC = {optimal_config['bic']:.2f}")

Covariance type meanings:

- Spherical: Same variance in all directions (circular clusters)

- Diagonal: Different variance per dimension (axis-aligned ellipses)

- Tied: Same covariance for all clusters (same shape/orientation)

- Full: Different covariance per cluster (most flexible, most parameters)

Pros and Cons

✅ Advantages:

- Probabilistic framework: Soft assignments are more realistic

- Solid theoretical foundation: Information theory based

- Accounts for model complexity: Penalizes overfitting

- Works with any likelihood model: Not limited to Gaussians (in principle)

- Well-established: Decades of research and applications

- Comparable across models: Can compare different model types

❌ Limitations:

- Assumes Gaussian distributions: Data must roughly follow this

- Computationally expensive: EM algorithm for each k

- Sensitive to initialization: May find local optima

- May favor too many clusters: Especially AIC

- Requires convergence: EM might not converge properly

- Not for all clustering types: Designed for mixture models

When to Use It

BIC/AIC are excellent choices when:

- Your data is continuous and roughly Gaussian

- You want probabilistic cluster assignments

- You need model comparison across different structures

- You’re doing generative modeling (e.g., synthetic data generation)

- You want to account for uncertainty in cluster membership

- Working with moderate-dimensional data (< 20 features)

Comparative Analysis: All Six Methods

Let’s now compare all methods we’ve covered across both Part 1 and Part 2:

# Summary table

summary = pd.DataFrame({

'Method': [

'Elbow Method',

'Silhouette Analysis',

'Davies-Bouldin Index',

'Calinski-Harabasz Index',

'Gap Statistic',

'BIC (GMM)',

'AIC (GMM)'

],

'Optimal k': [3, 2, 3, 3, 3, 3, 3],

'Agrees with Truth': ['✅', '❌', '✅', '✅', '✅', '✅', '✅'],

'Computation': ['Fast', 'Slow', 'Fast', 'Fast', 'Slow', 'Medium', 'Medium'],

'Statistical Rigor': ['Low', 'Medium', 'Medium', 'High', 'High', 'High', 'High']

})

print(summary.to_string(index=False))

Output:

Method Optimal k Agrees with Truth Computation Statistical Rigor

Elbow Method 3 ✅ Fast Low

Silhouette Analysis 2 ❌ Slow Medium

Davies-Bouldin Index 3 ✅ Fast Medium

Calinski-Harabasz Index 3 ✅ Fast High

Gap Statistic 3 ✅ Slow High

BIC (GMM) 3 ✅ Medium High

AIC (GMM) 3 ✅ Medium High

The Verdict

We now have 6 out of 7 methods agreeing on k=3! This is strong evidence that 3 is indeed the optimal number of clusters for the Iris dataset.

But what about Silhouette suggesting k=2? Let’s investigate:

# Compare k=2 vs k=3 in detail

from sklearn.metrics import silhouette_score, adjusted_rand_score

for k in [2, 3]:

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=42, n_init=10)

labels = kmeans.fit_predict(X_scaled)

sil = silhouette_score(X_scaled, labels)

ari = adjusted_rand_score(y_true, labels)

print(f"\nk={k}:")

print(f" Silhouette Score: {sil:.4f}")

print(f" Adjusted Rand Index: {ari:.4f}")

print(f" Inertia: {kmeans.inertia_:.2f}")

Output:

k=2:

Silhouette Score: 0.6810

Adjusted Rand Index: 0.5681

Inertia: 152.35

k=3:

Silhouette Score: 0.5528

Adjusted Rand Index: 0.7302

Inertia: 78.85

Aha! While k=2 has a higher silhouette score (0.68 vs 0.55), k=3 has much better agreement with ground truth (ARI: 0.73 vs 0.57). This reveals an important lesson:

Higher silhouette doesn’t always mean better clustering for your specific problem.

Silhouette measures geometric quality, but k=2 is likely merging two species that should be separate. This is why using multiple methods and domain knowledge is crucial.

Decision Framework: Which Method When?

After covering six methods, you might be wondering: “Which should I use for my project?”

Here’s my recommended decision framework:

1. Quick Exploration Phase

Goal: Get initial estimates quickly

Start with:

├─ Elbow Method (30 seconds)

├─ Calinski-Harabasz (30 seconds)

└─ Davies-Bouldin (30 seconds)

Result: Rough estimate of k range

2. Detailed Validation Phase

Goal: Confirm with statistical rigor

If methods agree:

├─ Silhouette Analysis (detailed per-cluster view)

└─ Gap Statistic (statistical validation)

If methods disagree:

├─ Try all methods

├─ Check assumptions (cluster shape, distribution)

└─ Consider domain knowledge

3. Reporting Phase

Goal: Justify choice to stakeholders

For technical audience:

├─ Show Gap Statistic (with confidence intervals)

├─ Report BIC/AIC (if using GMM)

└─ Include silhouette plots

For non-technical audience:

├─ Show Elbow Method (most intuitive)

├─ Mention Calinski-Harabasz (F-statistic analogy)

└─ Visualize clusters in 2D/3D

4. Special Cases

Very large datasets (n > 100,000):

- Avoid: Silhouette (O(n²)), Gap Statistic (too slow)

- Use: Elbow, Calinski-Harabasz, Davies-Bouldin

High-dimensional data (d > 20):

- Avoid: Distance-based methods (curse of dimensionality)

- Use: Model-based methods (BIC/AIC with dimension reduction)

Non-spherical clusters:

- Avoid: K-means-based methods

- Use: Dendrogram (Part 3), DBSCAN (Part 3)

Need probabilistic assignments:

- Use: GMM with BIC/AIC

Practical Example: Audio Quality Metrics

In my work at Jabra, I frequently cluster perceptual audio quality metrics. Here’s how I apply these methods:

# Simulated audio metrics (in reality, from GEMA framework)

np.random.seed(42)

n_conditions = 50

# Generate metrics with underlying structure

# Group 1: Spectral metrics

spectral = np.random.randn(n_conditions, 5) + [1, 0, 0, 0, 0]

# Group 2: Temporal metrics

temporal = np.random.randn(n_conditions, 5) + [0, 1, 0, 0, 0]

# Group 3: Perceptual metrics

perceptual = np.random.randn(n_conditions, 5) + [0, 0, 1, 0, 0]

audio_metrics = np.vstack([spectral, temporal, perceptual])

audio_metrics_scaled = StandardScaler().fit_transform(audio_metrics)

# Apply our methods

methods_results = {}

# 1. Calinski-Harabasz (fast screening)

ch_scores = []

for k in range(2, 11):

km = KMeans(n_clusters=k, random_state=42, n_init=10)

labels = km.fit_predict(audio_metrics_scaled)

ch_scores.append(calinski_harabasz_score(audio_metrics_scaled, labels))

methods_results['Calinski-Harabasz'] = range(2, 11)[np.argmax(ch_scores)]

# 2. Gap Statistic (statistical validation)

gaps, _ = calculate_gap_statistic(audio_metrics_scaled, range(1, 11), n_refs=10)

for i in range(len(gaps) - 1):

if gaps[i] >= gaps[i+1]:

methods_results['Gap Statistic'] = i + 1

break

# 3. BIC (model selection)

bics = []

for k in range(1, 11):

gmm = GaussianMixture(n_components=k, random_state=42)

gmm.fit(audio_metrics_scaled)

bics.append(gmm.bic(audio_metrics_scaled))

methods_results['BIC'] = range(1, 11)[np.argmin(bics)]

print("\nAudio Metrics Clustering Results:")

for method, k in methods_results.items():

print(f" {method}: k = {k}")

Key insight: For domain-specific applications, combine:

- Fast methods for initial screening

- Statistical methods for validation

- Domain knowledge to interpret results

Key Takeaways

After exploring three advanced statistical methods, here’s what you should remember:

- Calinski-Harabasz is your fast validator - O(n) complexity with solid statistical foundation

- Gap Statistic provides rigorous hypothesis testing - Can even detect “no clustering” (k=1)

- BIC/AIC are ideal for probabilistic clustering - When you need soft assignments and model comparison

- Consensus matters more than any single method - 6/7 agreement is strong evidence

- Higher score ≠ better for your problem - Always validate against domain knowledge

Methodological Principles

The three methods in this part share common themes:

Statistical Foundation:

- All based on established statistical theory

- Provide objective, quantifiable criteria

- Can be reported in scientific papers

Tradeoffs:

- More rigorous → slower computation

- More general → more assumptions to verify

- More sophisticated → harder to explain

Complementarity:

- Use fast methods (CH) for screening

- Use rigorous methods (Gap) for validation

- Use probabilistic methods (BIC/AIC) for uncertainty

What’s Next?

In Part 3 (final installment), we’ll explore:

- Dendrogram Analysis: Visual hierarchical clustering - finding k by cutting trees

- DBSCAN Parameter Selection: Density-based clustering without pre-specifying k

- Practical Recommendations: Complete workflow for real-world projects

- Case Studies: Applying all methods to different types of data

We’ll also provide a comprehensive comparison and decision flowchart to help you choose the right methods for your specific use case.

Discussion

What’s your experience with these advanced methods? Have you found cases where they disagree significantly? I’d love to hear about your use cases, especially if you’re working in:

- Perceptual evaluation (audio/video quality)

- Bioinformatics (gene expression clustering)

- Customer segmentation

- Anomaly detection

Drop a comment below or connect with me on LinkedIn!

See you in Part 3 for the finale!

Tags: #clustering #machinelearning #datascience #statistics #python #unsupervisedlearning #gaussianmixture

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: