Why Your Expensive Earbuds Spend More Engineering Effort on Your Zoom Calls Than Your Spotify Playlist

Think about the last time you bought a pair of premium wireless earbuds. You probably spent hours reading reviews, comparing frequency responses, debating between models. The marketing promised “studio-grade sound”, “deep bass”, “crystal-clear highs”. You imagined yourself lost in your favorite albums, hearing details you’d never noticed before.

And when you first tried them? The music sounded incredible.

But here’s what happened next. Within a few weeks, you found yourself using those earbuds for voice calls more than music. Work meetings on Teams. Quick calls with clients. FaceTime with family. Random WhatsApp calls throughout the day. And suddenly, what mattered most wasn’t whether the bass was punchy or the soundstage was wide. What mattered was whether the person on the other end could actually hear you clearly when you were walking down a noisy street, or whether your voice would cut out randomly during an important client call.

This is the paradox of modern audio products. We buy them for music. We judge them by their voice communication performance.

And after spending over a decade in the field of acoustics and audio, and now working as an engineer on consumer and enterprise products (TWS earbuds, headsets, videobars), I’ve come to realize something that most people outside the industry don’t know: the engineering team spends far more time, budget, and brainpower making sure you can talk clearly on a phone call than making sure your favorite song sounds perfect.

This isn’t marketing. This isn’t what we tell customers. But this is the reality of building audio products that actually survive in the real world.

The Consumer Perspective: We All Start With Music

Think about the last time you bought an audio product. Maybe it was a pair of wireless earbuds, or a gaming headset, or a Bluetooth speaker. What did you look at? The product page probably showed someone enjoying music, maybe dancing, maybe in a studio-like setting. The specs talked about frequency response, driver size, codec support. The reviews compared sound signatures, bass response, detail retrieval.

You probably didn’t think much about call quality. Maybe you saw it mentioned in passing: “Good microphone for calls”. But it wasn’t the main thing. The main thing was always the music.

I get it. I’m the same way. Music is emotional. Music is personal. When we think about audio products, we think about our favorite songs, our go-to playlists, those moments when a great song just hits different with good headphones. That’s the dream we’re buying into.

But then reality sets in. You’re on your third Zoom meeting of the day. Your colleague says “Sorry, you’re breaking up”. You’re on a call while walking to grab coffee, and the person on the other end says “I can barely hear you, there’s too much background noise”. You’re in your car, and suddenly your voice sounds like you’re in a tunnel. Or worse, the dreaded echo, where the other person hears themselves speaking back with a delay.

Suddenly, all those lovely bass frequencies and spatial audio features don’t matter. What matters is: can this thing make me sound like a normal human being when I’m trying to have a conversation?

This is where the rubber meets the road for audio products. And this is where most of the engineering effort actually goes.

Two Different Worlds: Music Playback vs Voice Communication

From an engineering perspective, music and voice are fundamentally different problems. And I mean fundamentally different, not just “oh they require slightly different tuning”.

Music: A Controlled, One-Way Path

When you play music, you’re dealing with a controlled, one-way signal path. The audio file exists. It’s been recorded, mixed, mastered in a professional studio. It’s been encoded with a codec like AAC, LDAC, or aptX. That file is transmitted to your device, decoded, maybe equalized based on your preferences, and played back through the drivers. Done.

The challenges are well-understood: minimize codec artifacts, tune the frequency response to be pleasing, manage power consumption during playback, maybe handle some spatial audio processing if you’re fancy. But fundamentally, it’s a solved problem. The music industry has spent decades figuring out codecs, and modern music codecs are really good. AAC at 256 kbps is transparent to most listeners. LDAC can go even higher. The signal chain is predictable.

Music is also forgiving. If there’s a tiny bit of distortion in the high frequencies, most people won’t notice or won’t care. If the bass is a bit too much or too little for your taste, you can adjust the EQ. If there’s a slight latency, it doesn’t matter because you’re not interacting with the audio in real-time. You’re a passive listener. You have control over when you play, pause, skip. The environment is usually somewhat controlled (you’re sitting, walking, or commuting), but you’re not trying to accomplish a critical task with the audio.

Voice: Real-Time Chaos

Now let’s talk about voice communication. Buckle up, because this is where things get complicated.

Voice communication is two-way, real-time, and happens in completely uncontrolled environments. Let me break down why this makes everything exponentially harder.

The Codec Situation: Speech vs Music

First, the codec situation. Speech codecs and music codecs are completely different beasts.

Music codecs like AAC or LDAC are designed for perceptual quality. They preserve harmonic structure, stereo imaging, frequency balance.

Speech codecs like Opus, AMR-WB, or the various codecs used by Zoom and Teams are designed for intelligibility and robustness at low bitrates. They prioritize making sure you can understand what someone is saying, even if it doesn’t sound “natural” in the audiophile sense.

Speech codecs operate at much lower bitrates because they have to work over networks with limited bandwidth and high packet loss. A typical music codec might use 128-320 kbps. A speech codec might use 8-32 kbps. To achieve this, they make aggressive assumptions about the signal being human speech: they model the vocal tract, they use aggressive compression. They sound fine for voice, but they would absolutely destroy music.

And here’s the kicker: your audio product needs to work with all of these codecs, across all platforms. Zoom uses its own codec. Teams uses another. WhatsApp uses Opus. Cellular calls use AMR or EVS. Your product doesn’t get to choose. It has to work with whatever the platform throws at it, and make it sound acceptable.

But the real complexity isn’t the codec. It’s everything that happens before and after the codec.

The Microphone Side: Capturing Voice in Chaos

Let’s start with capturing your voice. You’re on a call. Where are you?

Maybe you’re in an open office with colleagues talking nearby, someone typing on a mechanical keyboard, the HVAC system humming in the background. Maybe you’re in a coffee shop with the espresso machine hissing, background music playing, other people’s conversations overlapping. Maybe you’re at home with kids playing, a dog barking, traffic noise from outside. Maybe you’re in a car with road noise, wind buffeting the windows, the engine rumbling.

Your audio product has one job: extract your voice from this chaos and transmit it clearly to the other person.

This requires noise suppression, and not the gentle kind. We’re talking about aggressive algorithms that can distinguish between your voice and everything else, in real-time, without introducing artifacts or making you sound robotic.

Modern noise suppression uses machine learning. There are neural networks running on-device, trained on thousands of hours of noisy speech, learning to identify and preserve speech while suppressing everything else.

Beamforming: Spatial Filtering

But noise suppression alone isn’t enough. If you have multiple microphones (which most modern TWS earbuds and headsets do), you need beamforming. Beamforming uses the spatial arrangement of microphones to focus on sound coming from a specific direction (typically where your mouth is) and attenuate sound from other directions. This helps in multi-talker scenarios, like when you’re in a meeting room with other people, or when there’s a directional noise source like a fan or a person talking behind you.

Wind Noise: The Outdoor Nemesis

Then there’s wind noise. If you’re outdoors and there’s even a light breeze, wind buffeting the microphones creates low-frequency noise that’s extremely hard to remove without destroying your voice. Wind noise reduction algorithms detect the characteristic pattern of wind noise and suppress it, but they have to be careful not to suppress actual low-frequency speech components.

Transient Noise: Sudden Events

And there’s transient noise: sudden loud sounds like a door slamming, someone dropping something, a car horn. These need to be detected and suppressed quickly, within tens of milliseconds, or they’ll cause a jarring interruption in the call. But you can’t suppress too aggressively or you’ll cut out actual speech.

All of these algorithms need to run simultaneously, in real-time, with latency under 10-20 milliseconds, on a tiny chip with limited processing power and memory, all while consuming minimal battery.

And we haven’t even gotten to the hardest part yet.

Acoustic Echo Cancellation: The Silent Hero

Here’s a scenario: you’re on a call using your earbuds. The other person is talking, their voice is playing through your earbuds’ speakers. But some of that sound leaks out, or is transmitted through your head, and gets picked up by your earbuds’ microphones. If that sound gets transmitted back to the other person, they hear their own voice coming back at them with a delay. That’s echo. And it’s incredibly annoying.

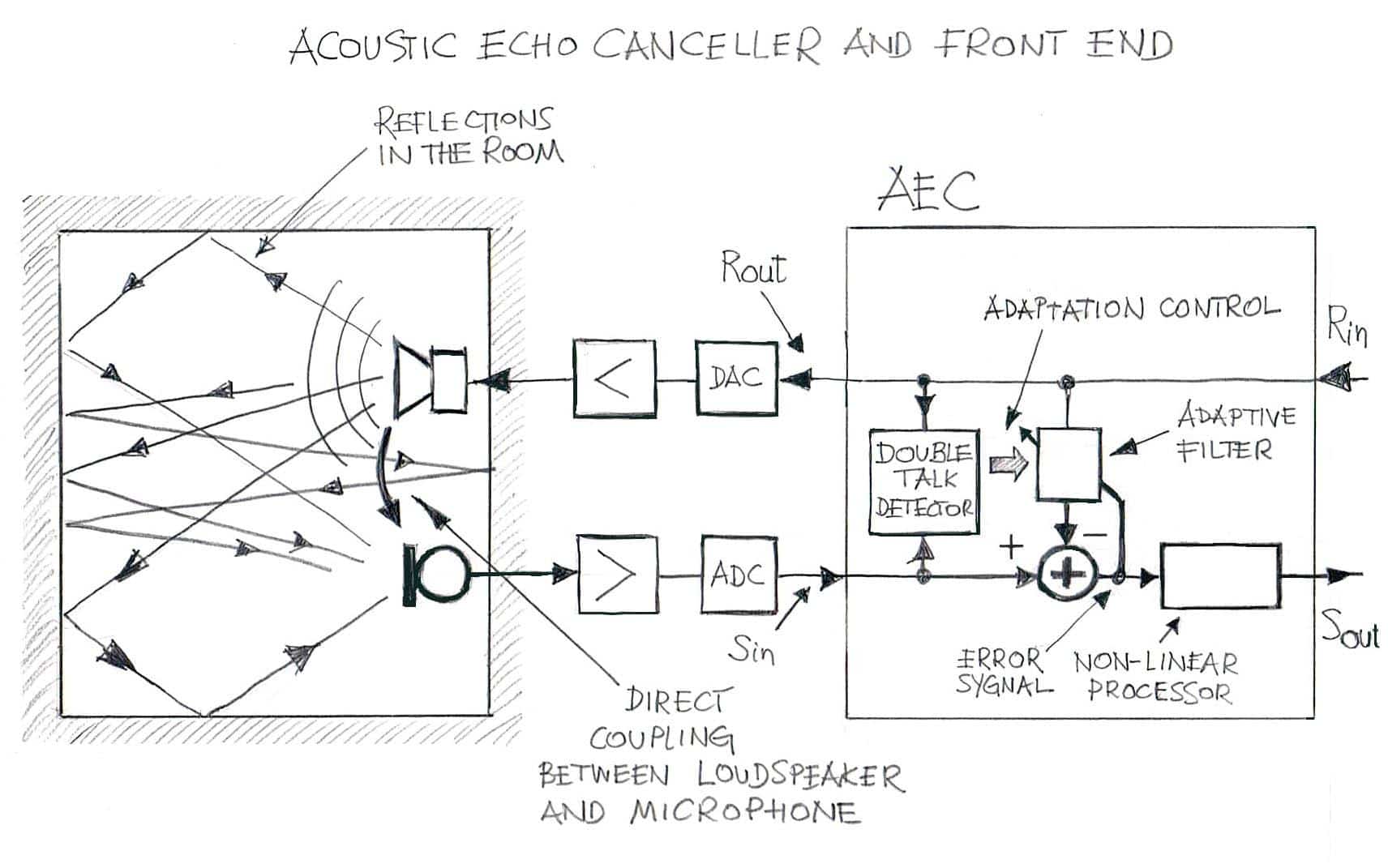

Acoustic Echo Cancellation (AEC) is the technology that prevents this. And it is mind-bogglingly complex.

How AEC Works (In Theory)

AEC works by maintaining an internal model of the path that sound takes from the speaker to the microphone. It takes the signal that’s being played through your speaker, predicts what that signal will sound like when it reaches the microphone, and subtracts it from the actual microphone signal. What’s left, ideally, is just your voice.

Sounds simple, right? It’s not.

The Adaptive Challenge

The acoustic path from speaker to microphone changes constantly. You move your head. The earbuds shift slightly in your ears. The ambient temperature changes the properties of the materials. The volume changes. Each of these affects how sound propagates.

So the AEC needs to continuously adapt its model of the acoustic path. This is done using adaptive filtering algorithms that are constantly updating thousands of filter coefficients in real-time.

Single-Talk vs Double-Talk

But here’s where it gets really tricky: single-talk vs double-talk.

Single-talk is when only one person is speaking. During single-talk, the AEC can be aggressive. If it only sees signal coming from the speaker side and nothing new in the microphone, it can confidently subtract out the echo.

Double-talk is when both people are speaking at the same time. During double-talk, both your voice and the echo are present simultaneously in the microphone signal. If the AEC is too aggressive, it will cancel out your voice along with the echo, and you’ll sound cut off or robotic. If it’s not aggressive enough, echo will leak through.

Detecting double-talk accurately and quickly is critical. You need algorithms that can distinguish between “this is echo that needs to be cancelled” and “this is actual speech that needs to be preserved”, in real-time, within milliseconds. And you need to transition smoothly between states. If the double-talk detector makes a mistake, the call quality instantly degrades.

Nonlinear Echo

Then there’s nonlinear echo. Most AEC algorithms assume the echo path is linear (meaning the relationship between the speaker signal and the microphone signal can be modeled with linear filters). But in reality, there are nonlinearities. The speaker can distort at high volumes. The microphone can have nonlinear response. These nonlinearities create harmonic distortion that the linear AEC can’t model. You need additional nonlinear processing to catch these residual echoes.

Use Case Variations

And all of this needs to work across different use cases:

- Earbuds, where the speaker is very close to the microphone

- Headsets, where there’s more distance but also more leakage

- Videobars, where you have multiple speakers and multiple microphones in a room with complex acoustics and potentially multiple people talking

- Smartphones in speakerphone mode, where the speaker can be quite loud relative to the microphone

The Make-or-Break Component

AEC is probably the single most critical component in a voice communication system. When it works well, it’s invisible. Users don’t even know it exists. But when it fails, even slightly, the call is ruined.

Echo is one of the most complained-about issues in audio products, and one of the top reasons people return products or leave bad reviews.

I’ve seen products with excellent music quality fail in the market because their AEC wasn’t robust enough. I’ve never seen a product succeed in the market with bad music quality but excellent call quality. Well, actually, I have. Business-focused headsets and videobars often don’t prioritize music quality at all, but they absolutely nail the voice communication, and they sell extremely well in their target market.

The Platform Compatibility Nightmare

Even after you’ve solved all the DSP challenges, there’s another layer of complexity: platform compatibility.

Your audio product needs to work seamlessly with Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Slack, Discord, WhatsApp, FaceTime, Skype, WebEx, regular cellular calls, and a dozen other platforms.

Each platform has its own quirks. Each handles audio slightly differently. Each has its own echo cancellation on the server side that might interfere with your device’s AEC. Each has different latency requirements and different packet loss characteristics.

Some platforms do aggressive server-side processing that expects relatively clean audio from the device. Others do minimal processing and expect the device to handle everything. Some platforms use variable bitrate codecs that adapt to network conditions. Others use fixed bitrate. Some prioritize latency, others prioritize quality.

Your product needs to be tested with all of these platforms. And not just tested in ideal conditions, but tested with packet loss, with jitter, with bandwidth constraints, with network switching, with all the messy real-world network conditions that users experience.

I’ve debugged issues where a product worked perfectly on Zoom but had terrible echo on Teams. Or worked great on Wi-Fi but had dropouts on cellular. Or worked fine in a quiet room but the noise suppression interacted badly with the platform’s own processing in noisy environments.

These are the kinds of issues that don’t show up in lab testing but become critical in real-world deployment.

Power Consumption: The Silent Killer

Here’s something most people don’t think about: battery life during voice calls vs music playback.

Music: Predictable Power Draw

When you’re playing music, the device is essentially just decoding a compressed audio stream and playing it back. The codec decoding is well-optimized. The DAC and amplifier consume a predictable amount of power. You can easily get 6-8 hours of music playback on modern TWS earbuds.

Voice: The Power Hog

But during a voice call, you’re running:

- AEC

- Noise suppression

- Beamforming

- Wind noise reduction

- Transient noise suppression

- Microphone amplification

- ADC

- Codec encoding

- Wireless transmission (both directions)

- Codec decoding

- Playback

And a lot of this is machine learning based, which means running neural network inference on-device in real-time.

All of this consumes significantly more power. It’s not uncommon for battery life during calls to be 30-50% shorter than during music playback. And users expect the battery to last through their entire workday of back-to-back meetings.

Optimization is Critical

This means every single DSP block needs to be optimized for power consumption. You need efficient implementations of adaptive filters. You need quantized neural networks that can run on low-power DSP cores. You need to carefully manage when to activate and deactivate different processing blocks based on the detected acoustic scenario.

I’ve worked on products where we spent months optimizing the power consumption of the voice processing pipeline, shaving off milliwatts here and there, just to get an extra 30 minutes of talk time. Because that 30 minutes can be the difference between making it through a long meeting or having your earbuds die right when you need them most.

The Budget Reality

So let’s talk numbers. I can’t share specific figures from specific companies (that’s confidential), but I can share the general industry trends I’ve observed working on various products over the years.

TWS Earbuds and Headsets

For TWS earbuds and communication headsets, roughly 55-70% of the audio R&D effort and budget goes into voice communication systems. This includes:

- Developing and tuning AEC

- Noise suppression

- Beamforming

- Microphone array design

- Testing across platforms

- Testing in various acoustic environments

- Power optimization for voice algorithms

- Validation with real users

Videobars

For videobars designed for conference rooms, the number is even higher, typically 70-85%. Videobars are especially demanding because they need to:

- Handle multiple speakers in a room

- Deal with challenging room acoustics

- Cover wider spatial areas with beamforming

- Integrate with enterprise platforms like Teams Rooms and Zoom Rooms that have strict requirements

- Work reliably in mission-critical business meetings where failure is not an option

Smartphones

For smartphones, voice R&D typically takes 50-65% of the audio budget. Smartphones are more balanced because music and media playback is genuinely important for the user experience, but voice calls (both cellular and VoIP) are still the primary use case for the audio system.

Music Gets What’s Left

The remaining budget (that 30-45%) goes to music and media playback:

- Speaker or driver tuning

- Frequency response optimization

- Codec support and optimization

- EQ presets and customization

- Spatial audio features (if available)

- Overall audio quality refinement

Industry Consensus

When I share these numbers with people outside the industry, they’re usually surprised. When I share them with people inside the industry, they nod knowingly. Because anyone who’s worked on shipping real audio products knows this is the reality.

What This Means for Everyone

For Engineers and Aspiring Audio Professionals

If you’re an engineer or someone considering a career in audio, come in with realistic expectations. I know many people enter this field because they love music, because they care about fidelity, because they want to create amazing audio experiences. That’s wonderful.

But understand that in real product development, you’ll spend most of your time working on voice communication. You’ll debug AEC more than you’ll tune bass response. You’ll run perceptual tests for noise suppression more than ABX tests for codecs.

And honestly? That’s not a bad thing. Voice communication engineering is genuinely challenging and intellectually stimulating. The problems are complex, multifaceted, and have real impact on people’s lives. When you build a system that lets two people have a clear conversation despite being in completely chaotic environments, that’s a real achievement. That’s technology that actually matters.

For Product Managers and Product Teams

If you’re a product manager or part of a product team, don’t underallocate resources for voice development. I’ve seen products fail not because their music quality was lacking, but because their call quality wasn’t reliable.

Users might buy your product because of marketing about “premium sound”, but they’ll keep it or return it based on whether they can actually use it for their daily calls.

For Consumers

And if you’re a consumer, next time you’re shopping for audio products, think beyond the music specs. Look for reviews that specifically test call quality. Test the microphone yourself if possible. Call a friend from a noisy environment and ask how you sound.

Because that fancy frequency response graph won’t matter much if your voice sounds like a robot during your next Zoom meeting.

The Paradox We Live With

There’s something almost poetic about this paradox at the heart of the audio industry.

We market dreams of musical perfection, of immersive soundscapes, of studio-grade fidelity. We show people enjoying their favorite albums, lost in the music, experiencing audio bliss. And that marketing works. People buy the products because of those dreams.

But behind the scenes, the engineering teams are in the trenches fighting a completely different battle. They’re wrestling with adaptive filters, training neural networks for noise suppression, debugging why AEC fails in a specific acoustic scenario, optimizing power consumption for real-time DSP, validating across dozens of communication platforms.

They’re not thinking about whether the bass is punchy enough or the soundstage is wide. They’re thinking about whether your colleague can hear you clearly when you’re on a call from a busy airport.

Both Sides Are Valid

And you know what? Both sides of this paradox are valid.

Music is important. It’s why many of us fell in love with audio in the first place. The emotional connection we have with music is real and valuable.

But voice communication is critical. It’s what makes these products useful tools rather than just entertainment devices. It’s what justifies the price tag when users are making buying decisions based on “do I need this for work?”

The Truth About Modern Audio Products

The truth is, modern audio products need to excel at both. But if I had to choose, if I could only get one right, I’d choose voice.

Because a product with mediocre music quality but excellent call quality can still be successful. A product with incredible music quality but poor call quality will struggle (unless it’s marketed purely as a music device with no expectation of voice use, and even then, users will try to use it for calls anyway).

Making Peace With Reality

After all these years in the industry, I’ve made peace with this reality. I still love music. I still care deeply about audio quality. But I’ve learned to appreciate the complexity and importance of voice communication systems.

I’ve learned that making two people able to talk clearly to each other, regardless of where they are or what chaos surrounds them, is actually a pretty amazing technical achievement. It might not be as romantic as chasing perfect fidelity, but it’s what keeps our products relevant in people’s daily lives.

So the next time you’re on a clear call from a noisy street, or your voice doesn’t cut out during a long meeting, or you don’t hear echo when someone else is talking, take a moment to appreciate the invisible army of algorithms working in the background.

That’s where most of the engineering effort went. That’s what’s keeping you connected.

Music might sell the product. But voice communication is what makes it worth keeping.

Tags: #AudioEngineering #VoiceCommunication #ProductDevelopment #TWS #AEC #NoiseSuppression

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: